Working in Wartime Industry

Thomaston's ethnically diverse male and female workers during World War I responded to the economic needs of the time.

By World War I, Thomaston’s industry had attracted immigrant workers from all over Europe; Germans, Poles, Swedes, Swiss, Italians, Irish, and others stayed in Thomaston for generations. Each group concentrated in certain types of work and sometimes lived in certain neighborhoods. However, ethnic lines were not sharply drawn. Most were within walking distance to the factories, and the common employer and lifestyle brought people of different backgrounds together much more than their ethnicities or religious traditions separated them.

Germans, many of whom were trained clockmakers from the Black Forest region, came to Thomaston to work at Seth Thomas from the Civil War to well into the 20th century. Some left Germany to avoid conscription. Bartholomew Albecker remembered in his WPA interview that when he arrived in New York in approximately 1890, he found the Seth Thomas office. He was hired because of his experience and took the train to Thomaston. This recruitment gave rise to a joke recalled as late as the 1980s – where the boats landed in New York, there was a sign that said “This way to Seth Thomas.” Albecker had worked at Seth Thomas for 48 years at the time of his interview in the late 1930s. He mentioned one particular “old” German named “Kaiser” who was already in Thomaston and working at Seth Thomas when he came, and that his son, E. R. Kaiser, was the first selectman at the time of his interview and had also been a supervisor at Seth Thomas. Another WPA interviewee, Arthur Botsford, corroborated these details. Unlike in other areas of the country, German heritage did not seem to raise much suspicion in Thomaston during World War I, likely due to the valuable contributions of German-Americans to Thomaston industry and society.

Thomaston had a large Polish population of both skilled and unskilled workers. John Mozonski came to Thomaston in the 1890s and worked at Seth Thomas and Plume & Atwood. He had five children who worked at Seth Thomas, including Stasia and Josie, who were interviewed in the 1980s. Stasia began working in the Marine Shop in 1917 at age 14. She worked in burnishing, which she remembered as messy, but not hard, work. Josie worked in assembly and a variety of other areas.

The Marine Shop employed other women, many of whom were ready to enter the work force for the first time during the war. For example, Matilda Barrett began manufacturing marine clocks in 1916 and spent the rest of her career at Seth Thomas.

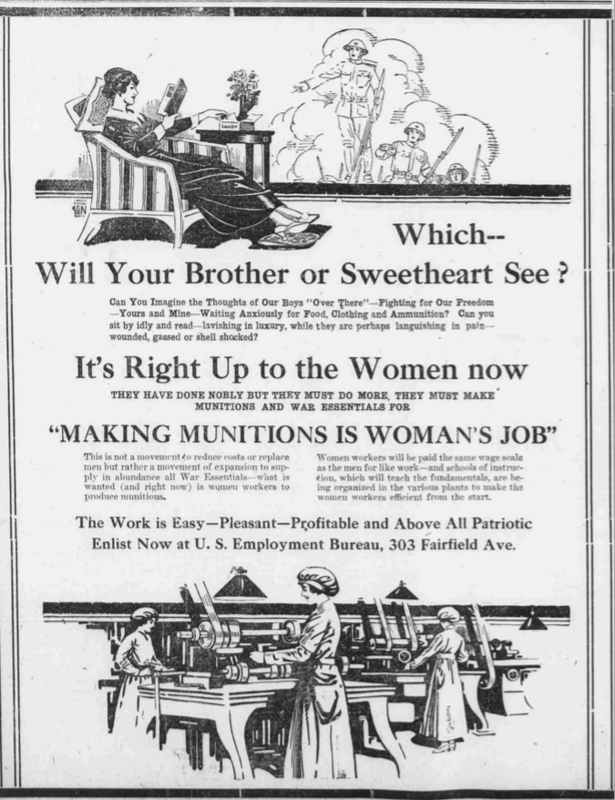

Stasia, Josie, and Matilda were among the 1 million American female industrial workers during World War I. In Thomaston and around the country, these were working class women; middle and upper class women who did not depend on a paycheck worked, often as volunteers, by being telephone and telegraph operators in France, Red Cross nurses or ambulance drivers, or Salvation Army “lassies” who served doughnuts to homesick soldiers.

Brass workers had dirty, difficult jobs. During the casting stage, metals were melted to form an alloy and then poured into a mold that created a flat bar called an ingot. The ingot proceeded to the rolling mill where the rollers changed its shape. In order to be rolled, the brass had to be heated in an annealing furnace and washed to remove surface impurities. Workers then cut the sheets of brass into the desired width. At the next stage, the brass strips were drawn through progressively smaller dies to create any size wire, rod, or tube. This wire, rod, and tube were the final products of most mills, but some manufactured specific items. Casters and rollers were skilled workers; mixing metals and timing rested on their judgment. Unskilled workers fired the furnaces (before electric furnaces were introduced during World War I) and carried the brass from one stage to another.

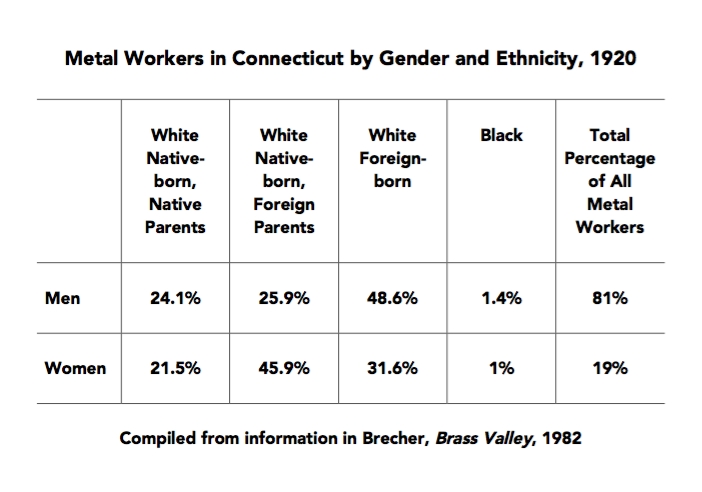

Brass mills were considered socially unacceptable places for (some) women, but when World War I increased the demand for laborers, such mindsets changed. Expansion of brass industry in wartime and contraction in peacetime meant that it utilized workers who were available to work when needed and who could be let go when not needed – women. The assumption was that women were not permanent workers, even though many were.

Propaganda posters like these that highlighted the importance of industry, shipping, and women might have appealed to Thomaston workers. George Creel of the Committee on Public Information, Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor, and Roger W. Babson of the propaganda arm of the Department of Labor aimed to convince American workers that it was their war and not the capitalists', while opposing socialism.

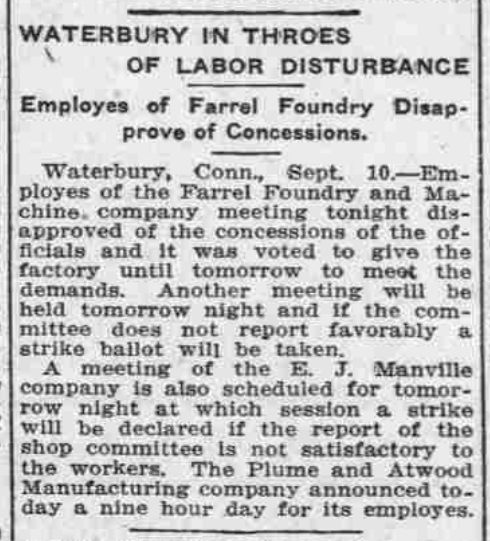

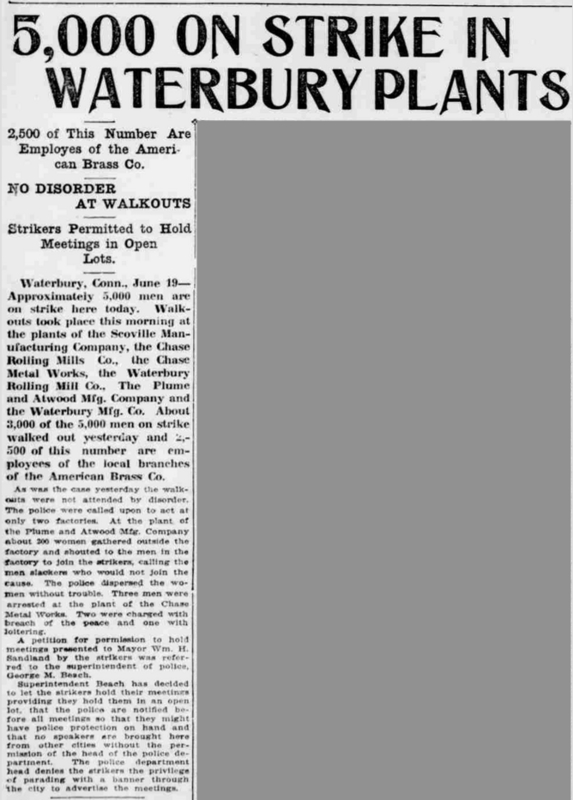

Workers around the United States took advantage of the opportunity to strike for better pay and conditions during the war.

Although there was a Knights of Labor local in Thomaston as early as 1886 as well as American Federation of Labor locals in Waterbury (including the Lady Brassworkers of Waterbury), brass companies maintained open shops until the 1930s. Strikes were rare in the brass industry during the war, but there was a strike of brass workers in Ansonia in 1916. Even the threat of strikes brought companies to capitulate; workers in Bridgeport at Remington Arms and the Union Metallic Cartridge Company and in Waterbury and Thomaston at Plume & Atwood achieved better pay and hours without having to strike in 1915. However, the end of World War I brought rapid inflation and the end of war production created uncertainty about employment and industry's ability to survive in peacetime, despite the War Industry Board's best efforts. This led to strikes in 1919 and 1920. As a result of the 1919 strikes in the brass industry, American Brass in Waterbury announced a wage increase and overtime pay. The other companies, including Plume & Atwood in Thomaston, followed suit.