Formation of the Woman's Land Army of America

While the farmerettes were gaining notoriety, there was still much progress to be made in the process of creating a structured organization. On June 4, 1917, an experimental facility called The Women’s Agricultural Camp opened in Bedford, New York. Over a period of 4 months, a total of 142 women, consisting mostly of college students, tradeswomen, and schoolteachers, learned how to farm and worked on local homesteads. The women were primarily city dwellers and lived together in the camp. After a physical examination, the women had a week of training in basic agricultural skills and became acclimated to physical tasks. Traveling in small groups, the women then worked locally wherever the farmers agreed to their conditions, namely an 8-hour workday and being paid the same amount as men, which was $2 a day. The camp provided the women with transportation to and from worksites as well as room and board and a monthly wage of $15. Led by Ida Ogilvie, a geology professor at Barnard College in New York City and a woman with an abundance of outdoor experience, the experiment was meant to figure out how to run the camp and how to persuade farmers to hire the women, which was difficult at first. However, as the summer progressed, word of mouth had spread the reputation of the hard-working women and the camp had to create a waiting list of potential employers.

After the success of the camp in Bedford, representatives from various organizations met in New York City to discuss the efforts of the women land workers. Just before Christmas of 1917, they formed the Woman’s Land Army of America and decided to work with existing federal organizations to find work placements. The organizational structure consisted of state branches formed in partnership with existing women’s organizations and state government. To help cover expenses, the WLAA held fundraisers and asked for donations from women’s groups. The organization also asked local schools and universities to provide agricultural classes and training. The YWCA helped with recruiting women to be laborers as well as older women to be leaders and supervisors of the WLAA units. Once the structure of the WLAA had been established, the women set about the work of promoting the organization with lectures, speaking tours, and the distribution of pamphlets. The next step was to get the support and recognition of the federal government. Despite a great deal of lobbying, however, the United States Department of Agriculture and the Department of Labor maintained that farm labor should be performed by men and would not acknowledge the WLAA, nor did the government provide funding. Although the organization did finally obtain a letter from President Woodrow Wilson endorsing the Women’s Land Army of America, the government as a whole remained unsupportive.

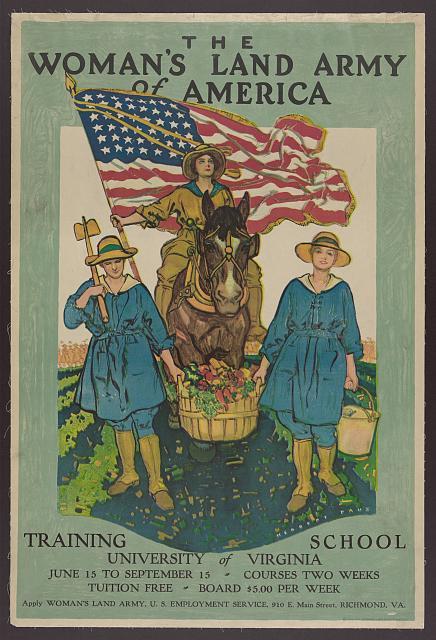

With food shortages still an issue in early 1918, the women of the WLAA set about recruiting laborers and encouraging the formation of state-level organizations. Farmerettes had received a fair amount of acclaim in the press for their work thus far but the WLAA’s organizers wrote letters to newspapers and articles in magazines to further raise their profile. Dressed in their uniforms, farmerettes traveled the country to speak about their experiences and the WLAA hung up colorful recruitment posters. While the organization was popular in the northeast, other parts of the country, like the Midwest and the South, did not embrace the idea of women in the fields. All the same, by the summer of 1918, there were 23 state organizations with 15,000 recruits.