Timely Brass Production

The brass industry in Thomaston and the Naugatuck Valley, already well established in the 1800s, boomed during World War I because of the needs of the time.

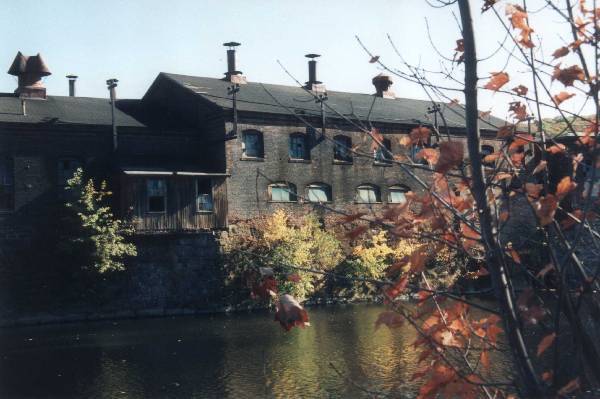

The brass industry in the United States began in the Naugatuck Valley for a few reasons. By the early 1800s, the War of 1812 and federal policy stimulated domestic industry and the clock industry in Thomaston and surrounding towns called for brass. Connecticut residents worked metals mined locally; this gave them some practice, but before long it was obvious that substantial amounts of raw material would need to be imported. One resource that the area did have was water. The brass industry originally needed the Naugatuck River for power. But even after the era of the waterwheel, brass mills needed water for washing the metal in the annealing process during which brass is heated and cooled every time it is rolled. Ultimately, the Naugatuck Valley had enough resources and enough incentive to develop the skilled labor that enabled it to remain dominant in the brass industry through the 20th century.

War created an unprecedented demand for brass. The Naugatuck Valley produced 75% of all ammunition cases made in the United States by 1890, but as late as 1900, the only substantial demand for brass was from clockmakers such as the Seth Thomas Clock Company. Clocks were more valuable in exports than all other brass products combined in that year. However, during World War I, the United States exported brass for the making of munitions. Brass exports totaled $300,000,000 and $250,000,000 during the war years of 1916 and 1917, respectively. The overwhelming majority of that brass came from the Naugatuck Valley. By 1922, it was down to $5,000,000 and that was mostly in clocks, once again.

World War I required brass for ammunition, artillery shell cases, and condenser tubes for boilers on ships. By early 1915, brass production had increased by 50%. By the end of 1915, brass production was double the highest it had ever been. In the summer of 1918 it was two and a half times the highest it had ever been prior to January 1915. War contracts from the United States and its allies accounted for this increase in production.

Many mills expanded their plants, utilized new machinery such as electric melting furnaces, and employed thousands of workers in order to meet the demand. However, there was still a shortage in brass tube. The War Industries Board intervened with a priority system and took over practical control of brass tube; if a company produced what the government needed, it was on a high priority list for getting the raw materials it needed.

Despite the government’s desire to protect postwar industry, many smaller mills went out of business after the war, and even older, established mills struggled. They were overbuilt, owed large sums of money, and many had to consolidate in order to survive. Plume & Atwood in Thomaston was one of the established mills and in the mid-1920s it was still one of the largest rolling mills in the country, producing 15,000,000 pounds per year.