Women in the Factories

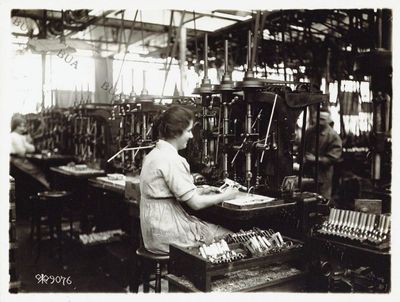

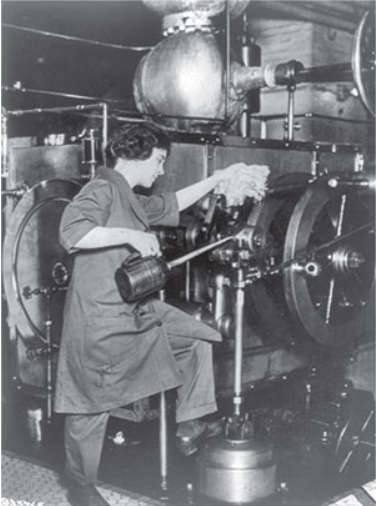

In the early 20th century, factory work was considered a man's job and few women were employed in the field. Once World War 1 began, this started to change. There was a significant increase in the number of women employed in factories and these women filled in a number of roles. They ran drill presses, did welding, operated cranes, used screw machines, and handled all manner of metal working equipment. Yet these women did more than just manual labor, they were also involved in production design, lab testing, drafting rooms, warehouse work, and driving trucks. The women shared the same risks as their male counterparts and did the same work. They were expected to produce at the same rate as the men, yet often times they were paid less for the same work. It is not uncommon that the idea of women workers in factories brings a person’s mind to World War II, but it was the Great War that the number of women in factories truly began to increase. It was not long after the war ended that American women who had tasted the freedom of independence that factory work gave them were given the right to vote. In 1920 the nineteenth amendment gave women the right to vote and the new powers and freedoms that women experienced during World War 1 expanded influence of the Women's Suffrage movement, along with the number of women in it.

David Drury, Hartford in World War 1.

Ferdinando Fasce, An American Family: The Great War and Corporate Culture in America.

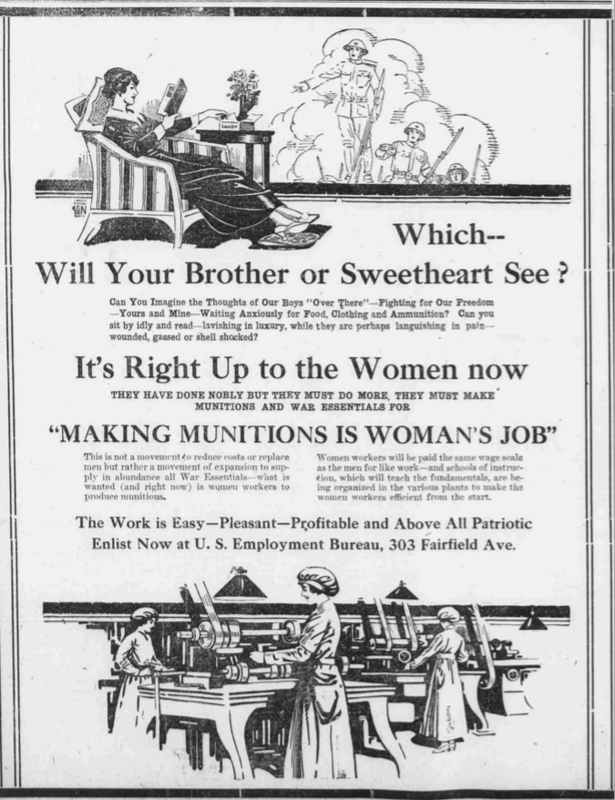

From 1914 to 1918 there was a significant increase in the number of people employed in factories in Connecticut. In 1913 there were 169,677 people in Connecticut employed in a factory; of this number 43,380 were women. By 1917 the number of people in Connecticut employed in a factory had increased to 355,994 with 86,991 being women. The number of women in factories had increased by 105% because thousands of men were leaving Connecticut to fight in Europe. These women were usually young with most being under the age of thirty. A draft was instituted in the United States in 1917 and Connecticut quickly provided a war time census for the government. This census included the number of men that would be able to fight in the United States military. Considering that the state was critical to war production, 54% of all ammunition for the United States military was produced in the state; it became difficult to meet the increased demand for war production while so many able factory workers were being sent to fight in the military. This drove companies to hire an ever-increasing number of women in what was considered a male-dominated job. In fact, the government’s Employment Bureau encouraged women to seek employment in factories. Yet many women faced discrimination on the job as they were often paid less for equal work and a large number of men saw women in their workplace as a threat to their own job security.

David Drury, Hartford in World War 1.

Ferdinando Fasce, An American Family: The Great War and Corporate Culture in America.

The need for women in factories was so essential for war production that the United States Government’s Department of Labor created the Women in Industry Service (WIS) in 1918. Industry had been increasingly disrupted by men being shipped overseas and the increased production requirements meant that women became necessary to the war effort. Due to the growing need for women in the factories the percentage of women in the workforce increased to 21% by 1920 and the occupations they were employed in expanded in range. The Women in Industry Service was an attempt to fill open factory positions to increase production. This would also allow extra men to be drafted because there were more people available to replace them. The Women in Industry Service attempted to accomplish this by coordinating with different organizations and corporations. This division of the Department of Labor was headed by Mary van Kleeck who was a college-educated woman as well as an adamant feminist. The Women in Industry Service had been established to solve a temporary problem but became a permanent part of the Department of Labor in 1920 when it developed into the United States Women’s Bureau. It was no coincidence that the bureau was created the same year as the passing of the nineteenth amendment which gave women the right to vote. The First World War gave women new freedoms and opportunities and led to growth in the influence of women’s rights organizations.

Women’s Bureau.

Not only were women joining factories as individuals to help the war effort, but many organized with other women. One such organization was the WWW (Women’s War Workers) and their members would wear a red, white and blue shield with WWW on top and USA below. This badge signified their devotion to the organization. Another organization was the American Red Cross which was founded in 1881 by Clara Barton. During the Great War the American Red Cross experienced rapid growth in both members and chapters. The number of chapters increased from 107 in 1914 to 3,864 in 1918. Their membership also grew from 17,000 to 20 million adult members and 11 million junior members. A large number of their members were women and a large number of them worked to produce war materials. In New Britain factories Red Cross workers made clothing for hospitals and refugees. The organization and the women in it were instrumental in the creation of the 300,000 gas masks manufactured in 30 days mentioned earlier. Yet manufacturing was not the only thing the Red Cross did to help the war effort. The organization sent 20,000 nurses to the front to help wounded soldiers and helped combat the influenza outbreak in 1918. There was a sustained effort on the part of the organization to fund relief efforts and to build hospitals. These funding efforts resulted in over $400 million raised by the Red Cross; this allowed the organization to have a tremendous impact on the war effort.

David Drury, Hartford in World War I.

The American Red Cross.

Despite the rising number of women in factory positions during World War 1, manufacturing work was still considered a man’s job. The few women that had worked in industry before the war were often the first to laid be off in tough economic times, such as the recession of 1913. Although there was no large economic recession at the end of the First World War, once men fighting in Europe began to return home in 1918 and 1919 they wanted their jobs back. This led to the layoffs of numerous women, more so because war production was coming to an end. Therefore, certain companies cut back on all production until peace time manufacturing demands were able to increase. This was easier for companies like Landers, Frary & Clark that already had a number of products that were for peace time production like cutlery and kitchen appliances. Colt on the other hand made guns in both peace time and war time. While demand for guns had been incredibly high during the war, it soon fell off in 1919. The overall workforce was cut back for the company and women were especially affected. It would not be long before women were again encouraged to work in factories. When war time factory production sky rocketed again in World War II, propaganda like Rosie the Riveter was used to spur women into working in factories. This is yet another example of how the First World War forever changed the way industry functioned in the United States.

David Drury, Hartford in World War I.